Git: the ironclad system

Laszlo Fogas

Hello everyone, Laszlo here from Gimlet.io 👋.

It's been a while when I learned git. Perhaps I am not the best one to relate to situations when you lose a day's work because git shenanigans, but I do recall occasions when colleagues with all different seniorities feared merging, conflicts or rebasing.

Now there are technologies even after fifteen years in this business which I google every time I use. Writing an if condition in bash? Installing a package on alpine linux? Gets me everytime. But git is not one of those.

Not because I know git inside out, but because I have a closed system where a minimum amount of knowledge keeps me safe. And if I wander from my safe space, I know how to get back.

I've been sharing my approach in the teams I worked in, and now putting it into a blog post. If you pick up a few things from it, I will be more than happy. It is not a git 101, but a general approach to organize your existing knowledge. With practical examples.

But first things first, it needs a fancy name: The Ironclad System 🤡. It is fitting: it is compact, it is closed, it is impenetrable.

Let's get into it. Shall we?

The ironclad checklist

This checklist puts the ironclad into git.

If you are able to answer these three questions, you will never get into trouble. Or if you are in trouble, you will know how to get back to safety. The three questions are:

- Where am I?

- What do I want to do?

- How to get back to safety?

These are the questions I percolate in my head before every git operation I do. Let's explore them now.

Where am I?

Before every git command, I need to orient myself. If I don't know where I am, I can't expect to get where I want to. This is especially true with git.

When you perform a git command, often you don't end up where you intended to, therefore run git status before every action. It is my single most used command with git.

Git is trying to help

I run git status before and after every command. Partly because my command may not do what I intended it to, and second, git is trying to help me. I know it feels just the opposite sometimes, but if you read the output of git status carefully, you will find possible commands that you could run next.

Like in this example with changes in my working copy. It tells how I can stage files to be committed, but also how to undo changes.

$ git status

On branch posts

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/posts'.

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: src/pages/blog/git-the-ironclad-system.md

In this more complex situation I tried to rebase my branch on main, but there were conflicts. Git is giving me very specific instructions on how I can

- resolve the conflict and continue the rebase

- or abort the change.

Auto-merging src/pages/blog/git-the-ironclad-system.md

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in src/pages/blog/git-the-ironclad-system.md

error: could not apply 7aab195... conflict

hint: Resolve all conflicts manually, mark them as resolved with

hint: "git add/rm <conflicted_files>", then run "git rebase --continue".

hint: You can instead skip this commit: run "git rebase --skip".

hint: To abort and get back to the state before "git rebase", run "git rebase --abort".

Could not apply 7aab195... conflict

Git history is a tree with pointers

Knowing the basics of git's data model will help you in your everyday git operations.

Git history is a tree. Its root is a single commit and all commits descend from it. Each commit knows its parent, and what diff it introduces to it. **

(**UPDATE: Kind Reddit people highlighted that technically git stores new versions of the files you change in a commit. Diff is calculated on the fly. For a mental model though, thinking of commits as a tree of diffs is still useful.)

When you branch out, you just create a new commit that has the same parent as another commit on another tree branch.

Branches. Branches are just named pointers. So as tags. So as main. They don't exist.

The only two properties branches have are their name, and the commit they point to. That is the branch HEAD, but if you think about it, branches don't identify any code tree. They identify a single commit, and that commit is on a tree branch. The identified commit knows its parent, the parent then knows its parent.. until we reach the first commit that has no parent. That's it, this is git's data model.

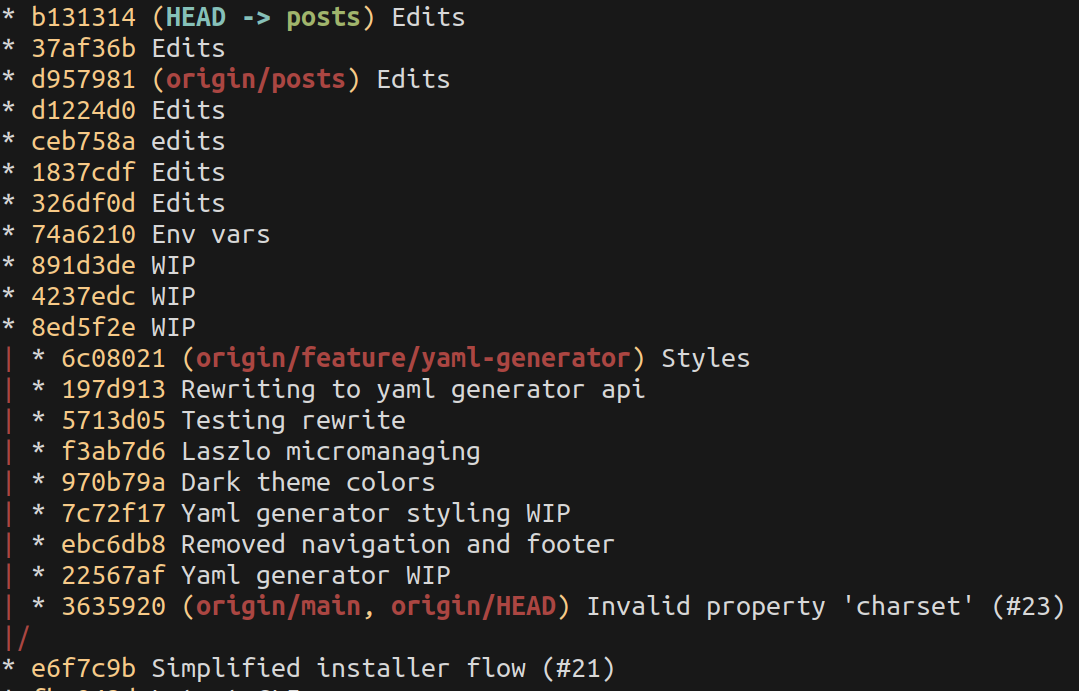

Now git has a great limitation in the command line. The default git log experience does not give you a good overview to reason about the code tree, so many people resort to git GUIs.

But git log is powerful, you only need an obnioxious amount of switches to make it useful. Here is my favorite:

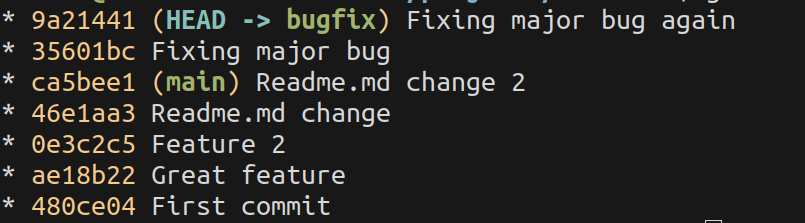

git log --graph --oneline --all

I created an alias for it in my ~/.gitconfig and named it git lola. Why lola? Not sure, I borrowed it from a colleague 12 years ago. Thanks Peter!

[color]

branch = always

diff = always

grep = always

interactive = always

pager = true

showbranch = always

status = always

ui = always

[push]

default = tracking

[log]

decorate = short

[pretty]

default = %C(yellow)%h%Creset -%C(auto)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr) %C(bold blue)%an%Creset

parents = %C(yellow)%h%Creset - %C(red)%p%C(reset) -%C(auto)%d%Creset %s %Cgreen(%cr) %C(bold blue)%an%Creset

[alias]

st = status

lola = log --graph --oneline --all

fp = fetch --prune

Git lola is my second most used command after git status.

Remote state

Git users often use git pull to get the latest version. But git pull does two things:

- it fetches the remote state

- then tries to bring your working copy up to date with the latest remote state by doing a merge.

It is much less error prone if instead of using git pull, you run git fetch first,then decide on the strategy to move your working copy version to the latest version.

git fetch fits better the ironclad system as it answers the where am I question and just that. Git pull on the other hand does not allow you to orient yourself before modifying your working copy and you may end up in states you didn't intend to.

I always run

git fetchto get the remote state- then a quick

git statusandgit lolajust to orient myself - and for quick fast-forward situations, I call

git pull --rebaseto get the latest version

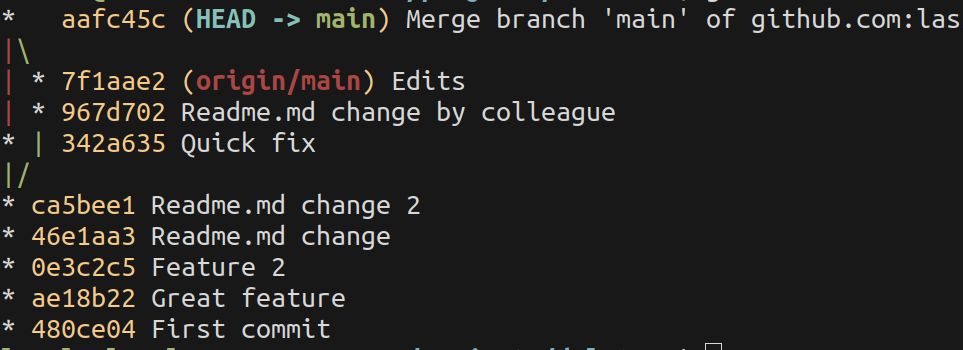

There is another problem with using git pull to get remote changes. If you and your colleague work on the same feature branch, git pull will do a git merge every time you get your colleague's commits. This complicates an otherwise straight line of commits with placing merge commits in the history.

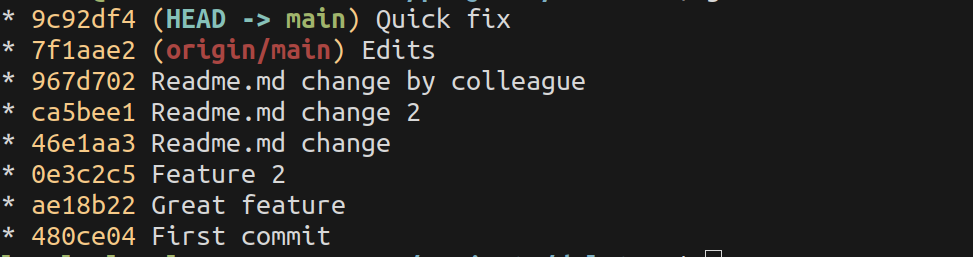

If you use git pull --rebase, git puts your unpushed commits on top of your colleagues changes and you always get a straight line in your history.

What do I want to do?

When you oriented yourself with git status and git lola and you know what you want to do, it is good if you have a couple of plans to get there. This section highlights a few lesser known techniques to extend your options.

Navigating

You certainly know how to change branches and move around in git. I just want to highlight a technique that quickens many navigation operations. It also has a risk of losing data, so it takes some practice to get a feel for it.

It is git reset --hard

- It throws away all working copy changes

- And sets a branch pointer to another hash

If you are on a branch and you want that branch to have the exact same state as another, you run git reset --hard <another branch>.

If you have various working copy changes and want to start over, you run git reset --hard HEAD. It resets your branch to the latest commit hash, thus throwing away working copy changes.

If you made a few commits locally on a feature-branch, but you realized it is a moot effort, you run git reset --hard origin/feature-branch. This throws away the commits that you recently made, and you can continue from the state that you have in the remote.

I use git reset and its --hard flag in versatile situations. There is just one thing to keep in mind. If a commit is not reachable from any pointer, aka branch or tag, that commit is gone. You can't get it back.

Staging

Staging is the process when you mark files to be included in the next commit.

git status is your biggest ally in this process, and as a reminder it also hints how you can add or remove files from the staging area. Besides git status, I run git diff a lot in this process.

- If I want to unstage a file, I use

git checkout path/to/file - or if I want to unstage all files and start over the staging process, I run

git reset HEAD. This time without the--hardflag as that would throw away all changes, while running reset without hard only resets the git staging area and it keeps my changes.

Integration

Integration is the process when you bring changes from a branch to the main code line.

There are two ways to bring code from one branch to another: merging and rebasing.

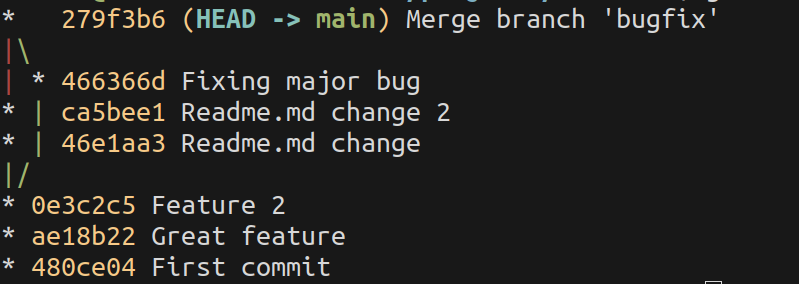

Merging

Merge is the straightforward way. You have two code tree lines, and they become one in the form of a merge commit.

This is the desired behavior when you integrate a feature branch to the main line. Anyone who browses git history will understand that a feature was developed on a branch and it was integrated at a given moment.

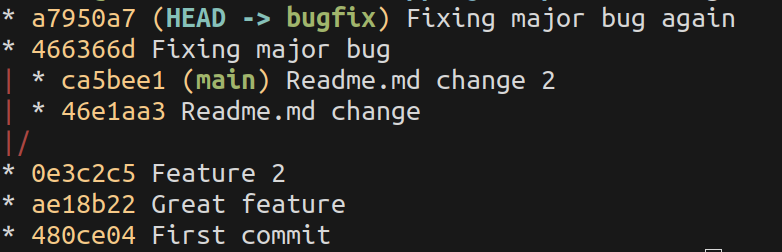

Rebasing

Other times history is less important than simplicity. A straight line of history is a lot easier to understand than a web of branches and merges. Those cases I favor rebase over merging.

Rebasing takes a commit line, cuts it at the moment of branch creation, and places on top of another branch. That way the history will be a straight line, and the fact that the code was originally written on a branch is discarded.

Before rebase, the feature branch and main:

After rebase, the feature branch cut and moved on top of main:

I often rebase when I am working alone on my branches, and historical correctness would not help anyone. Straight line histories do on the other hand.

There are edge cases when rebasing is a pain to use. Since rebase puts a branch on top of another branch commit by commit, you may have to resolve conflicts in every one of those commits. Sometimes you even have to resolve conflicts that happened earlier in your branch's life and are not part of the latest version. In those cases I just use git merge, and resolve the conflicts that exist in my final version of code.

Cherry picking

When I only want to integrate a single commit with another branch, sometimes I just take that one commit and place it on top of the target branch.

git cherry-pick <hash> is a quick way to integrate a single commit.

Squashing

When you experiment a lot, sometimes it is beneficial to keep the history clean of your experiments. Those cases you can squash your commits into a single commit.

git rebase -i HEAD~10 squashes your last ten commits into one. Since this process is -i interactive, mastering it can be difficult but worths practicing.

While practicing, sometimes you just want to give up and start over. Getting back to safety is a very important skill in git.

How to get back to a safety?

Things go wrong with git. Routinely. If your git status is not what you thougt it is, or there are conflicts, you have a situation to resolve. It gives you confidence if you know that whatever you try, you can always get back to a safe point and start over.

Git is trying to help

Remember, git is trying to help. The output of git status often contains possible next commands you can run. They are sometimes enough to get you out of trouble.

Even in the most complex rebase operations, git status suggests an option how to start over:

hint: To abort and get back to the state before "git rebase",

run "git rebase --abort".

Let's start over

When you want to get back to a safe state with git, you need to know if you have changes that are at risk.

If you don't, you can just git reset yourself out of the situation git reset --hard HEAD or git reset --hard main will get you to well known points.

If you have uncommitted changes, and you care about them, commit them first.

If you have everything committed, but you are doing branching operations you are not sure about, best to make a backup pointer to your current HEAD. git branch backup will create a restore point. Should you mess up something, you can git reset your current branch to the backup spot by git reset --hard backup.

Assumptions

This blog post worked with several assumptions. These are fairly known, but let me run through them so you better understand the context this system was meant to be used in.

Integrate often

No amount of git knowledge will save you from merge conflicts if they are building up for weeks across several branches. Best to integrate frequently and solve merge conflicts in small, manageable units.

Don't branch from branches

If your team frequently creates branches from branches, it will be a very complex task to integrate often.

Branching from branches also make git history complicated, making it difficult for you to orient yourself in git lola

Don't use git flow and friends

Branching strategies that build on long running branches go against best practices, causing unnecessary complexity for you to handle with git.

Onwards

This was a long one, if you picked up a few things from it, I will be more than happy.

Many people knows many git commands, but I find that sometimes they use it without a general concept. Hope answering the systems three questions help to be more mindful about your git approach.

Do you have a system? What does work for you?